THE 1689 CONFESSION: DOCTRINE AND UNITY

- Stephen McKay

- Nov 27, 2020

- 5 min read

“Christ unites, but doctrine divides.” Such has been the popular mantra in evangelical circles. In the early 18th century it was both Christ and doctrine that united the particular Baptists in the west of England, specifically, the doctrine contained in the 1689 confession.

Heterodox views on the doctrine of the Trinity and atrophy towards creeds and confessions was prominent in the first half of the 18th century. Confessions, many believed, were an attack on Christian liberty. Due to the way confessions had been used and abused by the state, it is understandable why many were opposed to confessional adherence. The disavowal of confessional adherence meant that there was an unhitching from past Trinitarian formulation. This led to disastrous effects on pastors and churches.

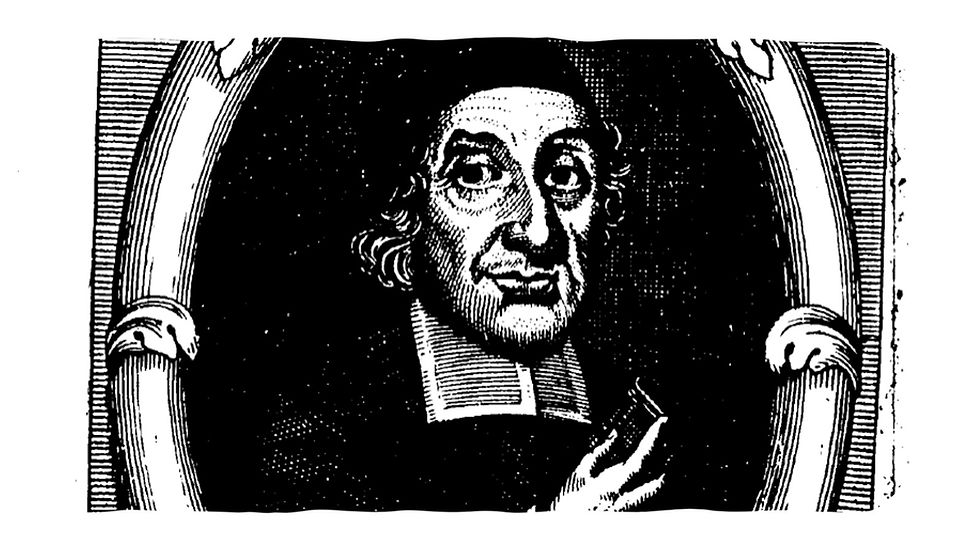

Joseph Stennett II (1692–1758) was a Baptist minister in Exeter during the Trinitarian/subscription disputes at Exeter (1717) and Salters’ Hall in London (1719). John Gill (1697-1771) acclaimed Stennett: “our young divine, as he then was, exerted himself with an uncommon and distinguished zeal at Exeter; made a noble stand for the proper divinity of our Lord, and appeared with great lustre and brightness in the defence of it.”[1]

Stennett was a faithful witness of the doctrine of the Trinity. He believed that the purpose of decrying the creeds and confessions of faith was the destruction of faith itself. This is because the gospel was so clearly articulated in the creeds, catechisms and confessions. Stennett went as far to state that the ridiculing of the catechisms was an attempt “to prevent the rising generation, from being acquainted, if possible, with the doctrines of the gospel.”[2] In 1733 he called readers to look at the trajectory that came from ministers rejecting confessions with contempt, and the prominence of many ministers fifteen years later that were not even friends of the Bible. If people were still baffled by the Trinitarian/subscription controversy at Exeter and Salters’ Hall in London, Stennett remarked, “yet time, I think, has put all this out of question.”[3]

Stennett became an influential voice for the Western Association (Baptist association). The Western Association before 1733 was united under the banner of Baptist without any particular regard to doctrine. Before the reconstitution of the Western Association in 1732–34, General or Particular Baptists with antinomian and hyper-Calvinist tendencies, or with Arian views, were allowed to be part of the one association.[4] But dissension in the Association eventuated in annual meetings that “were found to be rather pernicious than useful,”[5] and led to the Western Association being reconstituted under the Second London Baptist Confession of Faith (2LBC).

As early as 1721/22, Bernard Foskett (1685–1758) and the Broadmead Baptist Church recommended that the 2LBC should be a document for associating churches to affirm; however, it was not adopted. In 1732 Fosket and Hugh Evans (1712–1781) again proposed the omission of the broad acceptance of Baptists in the Association and a requirement to affirm the 2LBC. On 22 October in the same year, Fosket and Evans invited churches to form a new or reconstituted Western Association. In this letter their concern was the rise in Arianism, Arminianism, and other perceived heterodoxies, and their need to combat them with a public stand on the truths of the gospel. Stennett preached at the Association meeting in 1733.[6] He exclaimed, “it is, indeed, most shocking to consider that some, under the character of Christian ministers, instead of contending earnestly for the faith of Christ, are industriously sapping the fundamental principles of it.”[7] He contended for the affirmation and use of the 2LBC as a unifying document that binds true Christians to the sacred and important truths of the gospel:

The simplicity of the gospel, I think naturally requires this, and without it no communion can be secured from a mixture of persons of the most corrupt principles that have ever been advanced in the world.[8]

It was the Trinitarian debates in the early 18th century that led Fosket, Evans, and Stennett to advocate for a document thoroughly steeped in Trinitarian orthodoxy. Stennett believed “the ever blessed Trinity, is of the greatest importance to his glory.”[9] Any association was to be united under this fundamental truth. The Trinity was to be affirmed, Stennett remarked, by the “most excellent confession of our pious ancestors, in the year 1689, as the foundation of our future meetings.”[10] Article XIII of the reconstituted association states, “That we join together in association as agreeing in the Confession of Faith put forth by the Elders and Brethren of our Denomination in the city of London in the year 1689. As being we think agreeable to the scriptures. And we expect that every associating church do in their letter every year, signify their approbation of the said confession.”[11] It contended that no Christian society could be useful without fundamental agreement in doctrine. Without a thorough theological statement, the new Association believed that the greatest heretics in the world would associate and journey “with us, who own the Scripture but wrest ‘em to their own corrupt sense.”[12]

These churches were united under a confession that clearly articulated the gospel. They also believed that the association under a broad banner was not producing usefulness for the gospel. They desired a useful association, which is consistent with the 2LBC 26.14, when planted by the providence of God, so as they may enjoy opportunity and advantage for it, ought to hold communion among themselves, for their peace, increase of love, and mutual edification. The Western Association’s first article of agreement in 1774 confessed, the general end designed herein, is the cultivating and establishing mutual acquaintance with, aid and assistance unto, love and concord, amongst the Baptist Churches.

Adopting the confession took over ten years and teaches that change requires patience and time. Doctrinal unity on fundamental doctrines was the basis for adopting the 2LBC. They believed that to be useful meant to be united in truth, love, and communion with one another. The mutual love and care for one another is gospel action poured out in communion with other churches. When the church thinks of unity from Scripture it is naturally drawn to the goodness, and pleasant expression of unity in Psalm 133. Joseph Stennett’s son, Samuel (1727-1795), preached the funeral sermon for Caleb Evans (1737-1791), the principal at Bristol Baptist college between 1781-1791 and a contributor to the Western Association. Evans desired a useful association and a deep care for other churches; “Of him it might be said, that the care of the churches came upon him daily [2 Cor 11:8].” May pastors have the steadfast concern for other churches daily as they seek to be useful in their worship of the triune God, Father, Son, and Spirit.

[1]Gill, The Mutual Gain, 45. [2]Ibid., 16–17. Benjamin Wallin decried the same issue referencing the Salters Hall Synod in 1771 in his Scripture Doctrine of Christ’s Sonship—“a party Spirit gave the enemy an advantage; from that time, in zeal against tests of this kind, catechisms, creeds and confessions of faith, have been decried as injurious to liberty, this falling in with a taste for pleasure, and an aversion to discipline, has greatly obstructed a religious education among us, insomuch that the present rising generation, through ignorance, are exposed to the subtlety of every deceiver”: Wallin, Christ's Sonship, xii. [3]The Christian Strife,16–17. [4]Hayden, Continuity and Change, 30. [5]Ibid. [6]Stennett was a Seventh Day Baptist. Despite the disagreements with other Particular Baptists, Seventh Day sabbath observance was one of two issues the Western Association did not divide over (praise singing being the other). Note that this was not an indifference towards the doctrine, but a concession on when the Sabbath was observed (either Saturday or Sunday). [7]The Christian Strife,78. [8]Ibid.,16. [9]Ibid., 21. [10]Continuity and Change, 34. [11]G98a Wes, Western Association notes, Bristol Baptist College Archives. [12]Ibid. [13]“Mortality of Ministers,” 40.

Comments